The Weird Story of Standard Oil

Table of Contents

Once upon a time, the US government enforced antitrust legislation. One of the most famous examples of this is the case of Standard Oil, which remains the textbook example of monopoly breakup taught in economics and law schools worldwide.

To understand what happened to Standard Oil, we need to take a short walk back in time through history. The year is 1890, and the US Congress is a well-functioning body with rational officials whose brains still function at a high enough level to pass sensible legislation.

The Sherman Antitrust Act passed the Senate by a vote of 52-1, as most politicians agreed that competition is good and business should not engage in anticompetitive behavior. Few would disagree with that assertion, and those who do tend to be the greedy selfish type who would love to watch the world burn if it means they get a few more dollars to hoard in their bunkers.

The general consensus in the government at the time was that society should move forward for everyone, not just like 3 or 4 guys who own more than 50% of the population. During the Gilded Age, income inequality had reached levels comparable to today, with the top 1% of Americans holding approximately 45% of all wealth.

John D. Rockefeller in 1872, after founding his new startup1

Fast forward to 1896, when John Rockefeller, founder of Standard Oil, decides it’s time to retire, but he retains his position as president and major shareholder. By 1904, Standard Oil has grown to control 91% of refining capacity and 85% of sales for oil & gas products. According to economic historians, Standard Oil achieved this dominance through a combination of predatory pricing, industrial espionage, and secret transportation rebates that smaller competitors couldn’t access.

Now here’s where it starts to get interesting. Standard Oil was on the radar of antitrust regulators fairly early on, but Rockefeller was a slippery man who used legal tactics and maneuvering to make it harder for the government to do anything about the obvious monopoly Standard Oil had. Some of those tactics included converting Standard Oil into a trust in 1882, 8 years before the Sherman Act passed.

Unfortunately (or rather, fortunately, if you read on) for Rockefeller, US lawmakers didn’t stutter and the Sherman Act explicitly prohibited using trusts to get around limits on monopolies (hence the term “antitrust”).

In 1899 Rockefeller tried one more trick which was to convert the trust into a holding company composed of 41 other companies. That didn’t save them, however, and even though Standard Oil’s market share began to fall, by 1911 the Supreme Court ordered Standard Oil to be broken up into 34 independent companies in Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States.

Up to this point, Rockefeller was already insanely rich. But after Standard Oil was broken up, his wealth grew immensely. By 1913 (2 years after Standard Oil was broken up), his wealth was about 3% of the total US GDP – approximately $418 billion in today’s dollars.

To this day, no one (not Elon, not Jeffrey) has come anywhere close to Rockefeller in terms of wealth as a percentage of GDP. Musk’s wealth at its peak represented approximately 0.9% of US GDP, less than a third of Rockefeller’s economic footprint.

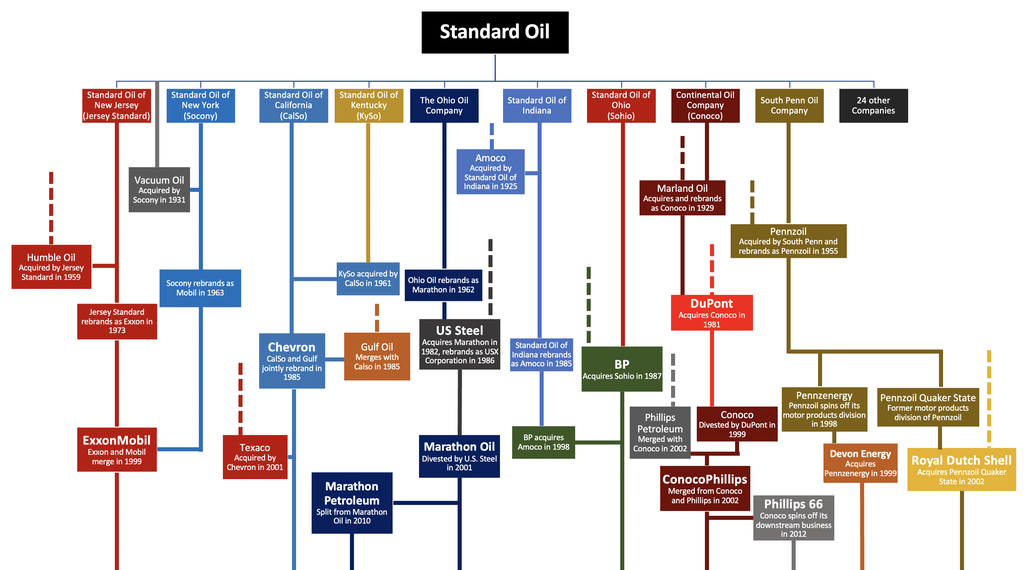

The weird thing that happened after the breakup of Standard Oil was that many of the baby Standard Oils went on to become very successful, and they competed with each other, creating a more dynamic and innovative oil industry. Economists point to this as evidence that breaking up monopolies can actually increase overall market value rather than destroying it.

Baby Standard Oils, in 20222

Although Rockefeller’s wealth doubled in a short matter of time after the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911, his wealth peaked in 1913 and he spent the rest of his 40-some years relaxing on his baller estate in Westchester County and giving away substantial portions of his fortune to various philanthropic causes.

Even today, some of the Standard Oil babies make up some of the biggest companies in the world. Notably, ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Marathon are among the top 50 companies in the world by revenue.

When those companies aren’t busy purveying climate disinformation (as documented in an investigation by Harvard researchers), they’re quickly destroying our planet by filling our air, soil, and water with toxic byproducts. Although I guess that’s not really what this story is about.

Fast Forward to Today #

And now here we are, once again faced with a situation where a few entities control a significant share of their respective markets. Google has a monopoly on web search (with approximately 90% global market share), advertising, web browsers, and Apple and Google together have a duopoly on internet-connected mobile computers (aka “cell phones”). There are more examples, but those are the big ones.

You can certainly make some weak arguments against that, but you probably can’t do it without doing a Google search and seeing some Google ads with Google Chrome, and if you’re on mobile you’re either using a Google phone or an Apple phone, and if you’re on iOS then you have to use Apple’s Safari to browse the internet (all the non-Safari branded browsers on iOS are still Safari, with different skins, including Chrome and Firefox and everything else, which is why so many websites don’t work properly on iOS because Safari on iOS is intentionally crippled to force you to install “apps” instead), and you can’t install a proper adblocker on iOS because Apple doesn’t let you choose what software you’re allowed to run on your own hardware that you purchased and own and yet it’s still not really yours because if you do anything with it that Apple doesn’t like it will stop working and you’re SOL.

The parallels to Standard Oil are striking. As Yale Law Journal notes, today’s tech giants employ many of the same tactics: predatory pricing (selling at a loss to destroy competition), vertical integration (controlling every aspect of their supply chains), and using their platforms to preference their own products over competitors'.

Yet unlike the era of Rockefeller, modern antitrust enforcement has been largely toothless. The prevailing “consumer welfare” standard established in the 1970s focuses almost exclusively on whether prices increase for consumers—difficult to apply to companies like Google and Facebook that provide “free” services while extracting enormous value from user data.

Maybe we need a new Sherman Act for the digital age—one that recognizes that monopoly power can harm society even when it doesn’t directly increase consumer prices. Or maybe we just need regulators with the same backbone as those who took on Standard Oil over a century ago.

Okay, I’m done now, thanks for reading.

By Unknown author - books.google.com/books?id=zaYZAAAAYAAJ, Public Domain, link ↩︎