The Arduous Path to Mastery

Table of Contents

I have a deep appreciation for mastery. It takes an extraordinary amount of time and effort to become truly masterful at something. It doesn’t matter so much what that thing is, whether it’s a sport, a musical instrument, a language–spoken, written, or programming computers. The path to mastery is the same: it demands time, practice, sweat, tears, trials, tribulations, and a whole lot of hard work.

I admire people who have achieved mastery in their endeavors, and I especially admire those who have achieved mastery in multiple domains. Leonardo da Vinci, for example, is known for his work in painting, sculpture, architecture, science, music, mathematics, engineering, literature, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, writing, history, and more. How this man found the time, who can say, but perhaps he invented a time machine and found a way to extend his life while telling no one.

The 10,000-Hour Reality #

The popular notion that mastery requires 10,000 hours of practice gained widespread attention through Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers.” While subsequent research has shown this figure isn’t a perfect universal threshold, there’s truth in the underlying principle: mastery requires an enormous time investment. The Florida State University psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, whose work Gladwell based his rule on, found that elite performers across various fields typically engaged in at least 10,000 hours of “deliberate practice”–focused, structured activities specifically designed to improve performance1.

I wouldn’t quite say that I’m a master of anything, but I have become quite good at a few things. I’ve been programming since I was 12 years old, and I’ve been doing it professionally since I was 16. I’ve also been doing some sort of creative writing since I can remember. I’m not sure that I’m good at either, but I do at least feel somewhat competent in both.

Let me try and make a ballpark estimate of the time I’ve spent programming, for example. Since I started at 12, and I’ve managed to stay alive for 39 years since my birth, that’s about 27 years of programming. If we conservatively estimate that I’ve programmed for an average of 20 hours per week, that’s about 28,080 hours of programming.

$$ 20 \text{ hours/week} \times 52 \text{ weeks/year} \times 27 \text{ years} = 28,080 \text{ hours} $$

The real number could be more or less, but this is a good starting point. Sometimes I program more, sometimes less, but I feel like 20 hours per week is a good average across all time.

I think the only reason I’ve managed to keep programming for so long is that I’ve been able to find ways to make it fun. I’ve also been able to find ways to make it feel like progress, even when I’m not actually accomplishing anything. I try to always be learning, and the process of learning itself is a real passion of mine.

The Quality of Practice Matters #

Modern research shows that the quality of practice matters as much as quantity. What Ericsson termed “deliberate practice” differs from mere repetition. It involves:

- Working on specific aspects that need improvement

- Receiving immediate feedback

- Consistently pushing beyond your comfort zone

- Mental representations of the desired outcome

- The guidance of expert teachers or coaches

Consider the contrast between a pianist who mindlessly plays the same pieces for 20 years versus one who systematically tackles increasingly difficult compositions, analyzes technical weaknesses, and regularly performs for critical instructors. Though both might practice the same number of hours, their outcomes will differ dramatically2.

Historical Masters and Their Obsessive Dedication #

History is filled with examples of masters whose dedication bordered on obsession:

Johann Sebastian Bach copied other composers’ scores by moonlight as a child when denied access to them, damaging his eyesight but developing a profound understanding of musical structure. His dedication extended to walking 250 miles(!!) to hear the renowned organist Dietrich Buxtehude perform3.

Marie Curie worked in such primitive laboratory conditions that she developed aplastic anemia from radiation exposure, eventually giving her life to her scientific pursuits while becoming the first person to win Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields4.

Michael Jordan, despite being cut from his high school varsity basketball team as a sophomore, famously responded by practicing even harder. His trainer Tim Grover revealed that Jordan would demand practice sessions at 5:30 am and then practice again after team practices while others went home. His obsession with improvement never diminished, even at the height of his success5.

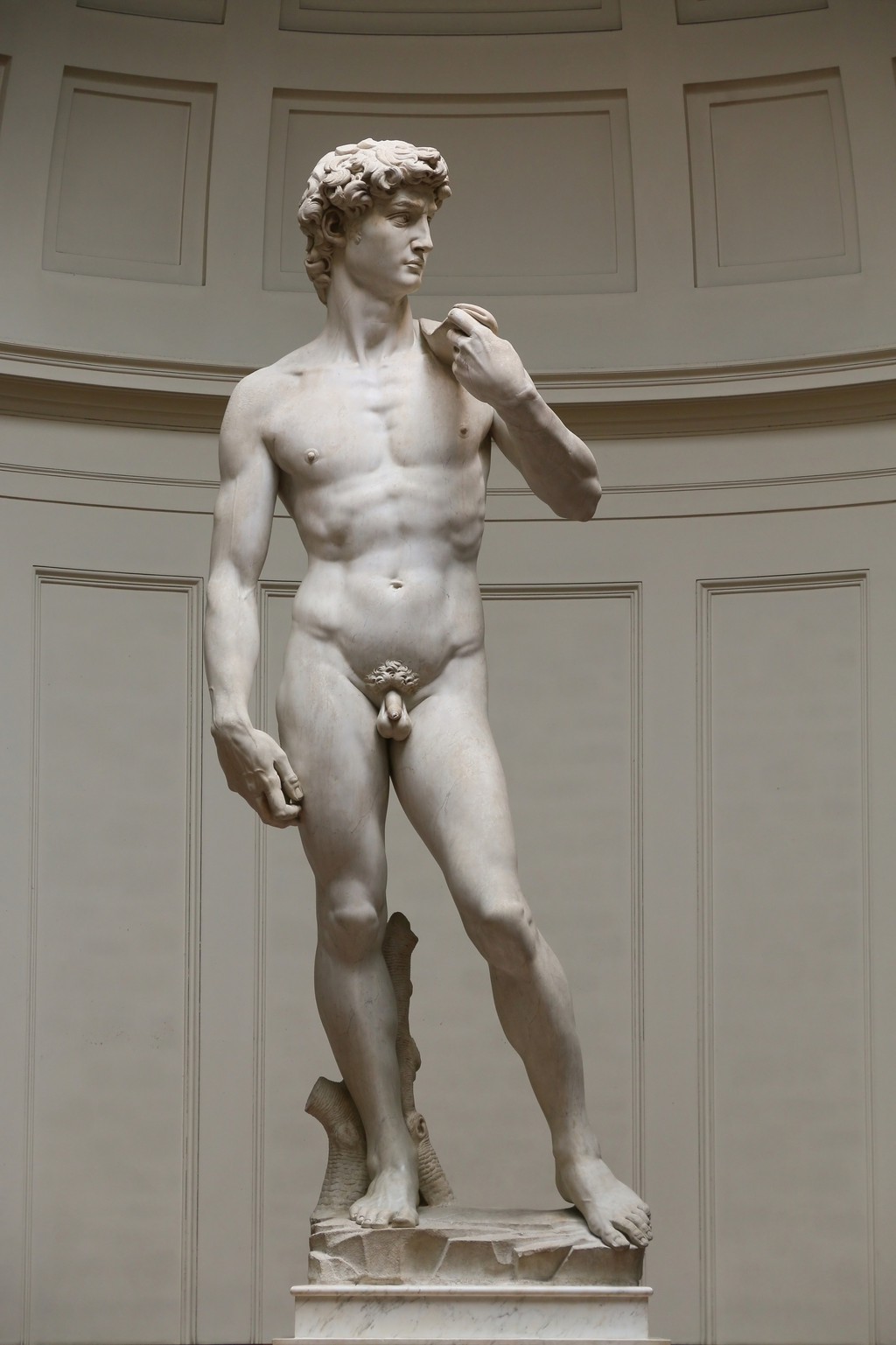

Michelangelo’s David6

Michelangelo spent four years painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, developing a permanent neck deformity from looking upward for hours each day. When not painting, he dissected corpses to understand the human body better, a practice that was both illegal and dangerous at the time, not to mention creepy and weird7. Michelangelo’s David took approximately 3 years to complete, and he was 29 years old at the time.

Sticking to It: The Valley of Disappointment #

I think a lot of people give up on their goals because they don’t see immediate results. They don’t see the progress, and they don’t feel like they’re getting anywhere. It’s easier to quit and go back to Netflix or Instagram than it is to stick it out through the hard times, the plateaus, and the frustration. I know this because I’ve been there, I’ve not only quit many things, but I’ve also experienced long periods without progress, including negative progress, and I’ve had to work through them.

This phenomenon is so common that psychologists have given it a name: “the Valley of Disappointment.” It’s the phase where your expectations outpace your abilities, causing frustration and often abandonment of the pursuit. Researcher Herminia Ibarra found that this gap between aspiration and current ability represents a critical juncture in skill development – those who persist through this uncomfortable phase eventually reach breakthrough moments, while those who retreat never discover what might have been possible8.

Going deep on anything is hard. It’s easy to do a half-assed job on just about anything, but to become a real artisan, an expert, a master, it takes extreme focus, dedication, passion, time, and work. When you look at people who are masters of their craft, they tend to be exceptional, remarkable people, often to the point of being eccentric, possibly even obsessive.

The Neurological Basis of Mastery #

Recent neuroscience research helps explain why mastery requires such extensive practice. Skill development involves myelination–the process where neural pathways are insulated with fatty tissue, allowing electrical signals to travel more efficiently. This physical restructuring of the brain happens gradually through consistent practice, creating what we experience as effortless expertise.

Dr. Daniel Coyle, in his book “The Talent Code,” describes how myelin functions as “broadband for your brain,” letting signals travel up to 300 times faster along well-insulated neural pathways. This physiological process explains why mastery cannot be rushed – the brain literally requires time to build these physical structures9.

The Lonely Path and Psychological Costs #

It’s isolating to be a master. Spending an enormous amount of time on something means taking time away from other things, perhaps family, friends, and even yourself. This hasn’t even been a problem for me as I’ve never really had much of a social life, which I suppose lends itself to the path of the master. Whether I’m lonely because I spend so much time on something, or because I don’t have much of a social life, I don’t know. I think in reality it’s a bit of both. If I did have something better to do with my time I’d probably do that thing, but really I do not.

I spent my childhood and adolescence in a constant state of loneliness, and I’ve never really been able to shake it. I coped with that loneliness by immersing myself in the Internet and computers. So in a way, while I may have some valuable computer skills, I’m somewhat ashamed of why I have those skills. I don’t necessarily view it as something to be proud of, but rather something to be embarrassed about.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, known for his research on “flow states,” found that many masters experience this double-edged nature of expertise. The same deep immersion that creates transcendent experiences of flow often creates distance from ordinary social connections. His research on creative geniuses found that many experienced profound social isolation as both a catalyst and consequence of their dedication10.

The Eccentricity of Masters #

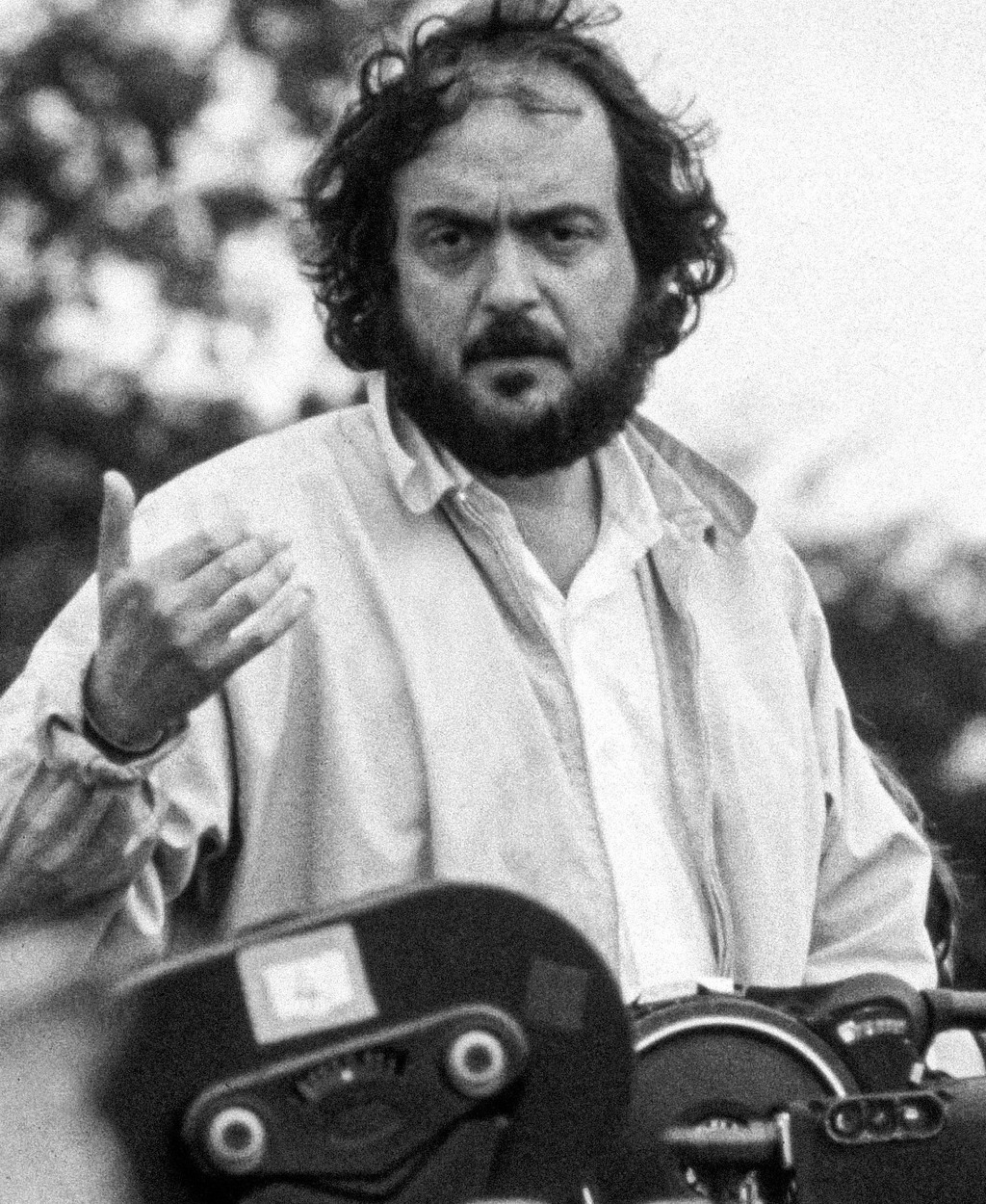

Stanley Kubrick on the set of the 1975 film Barry Lyndon11

There are quite a few interesting historical examples of people who mastered their craft, and in many cases they were known to be unusual, difficult, or even destructive individuals.

Stanley Kubrick produced some remarkable films, but he was also known to be extremely difficult to work with to the point of being a nightmare to work for. He demanded insane hours of his crew, sometimes to the point of abuse. During the filming of “The Shining,” he famously made Shelley Duvall repeat a simple scene 127 times, driving her to the point of physical exhaustion and emotional breakdown–a state he then used to capture authentic distress on film12. A small price, perhaps, for a few minutes of priceless entertainment. And I suspect Shelley Duvall looks back fondly on the experience, even if she perhaps shouldn’t.

Ludwig van Beethoven would often forget to eat during creative periods, and was known to pour cold water over his head when composing to stay alert, soaking both himself and the floors below. His notebooks show he would write the same musical phrase dozens of times with minute variations until finding precisely the right expression13.

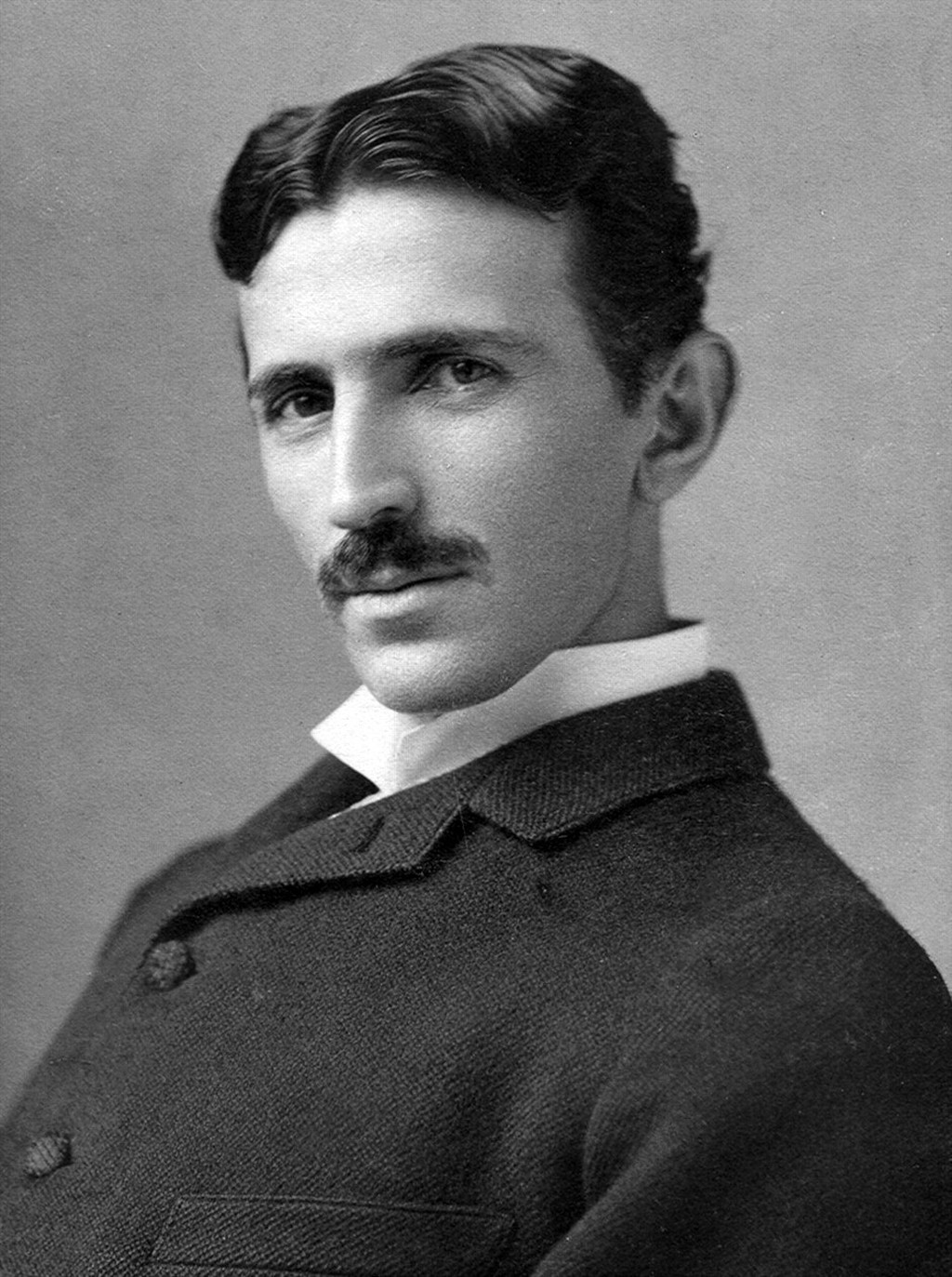

Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) at age 3414

Nikola Tesla developed numerous bizarre rituals, including his insistence on only staying in hotel rooms with numbers divisible by three and his compulsion to circle a block three times before entering a building. Despite–or perhaps because of–these eccentricities, he developed revolutionary theories about electricity that were decades ahead of his time15. He may have also just been a lunatic.

Howard Hughes, the aviation pioneer and film producer, was known for his increasingly severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. He would spend days in a darkened screening room, naked and unwashed, watching movies repeatedly while living on nothing but milk and chicken. Despite his deteriorating mental state, his innovations in aircraft design revolutionized aviation, and his films pushed the boundaries of what was technically possible in cinema16.

Glenn Gould, the renowned classical pianist, was famous for his peculiar habits. He would only perform while seated in his father’s old chair (which he carried everywhere), hummed loudly while playing, and insisted on keeping the temperature at exactly 80 degrees Fahrenheit. He would soak his arms in hot water for 20 minutes before performances and wore winter clothing in summer. Yet his interpretations of Bach’s works are considered among the most innovative and influential of the 20th century17.

But Why? The Psychology of Mastery Pursuit #

I think most people who choose to dedicate their lives to mastering something do so because they have a deep passion for it. In some cases, it may be because they feel they have to prove something to themselves or others. In other cases, it may be because they have a genuine love for the craft. In other cases, people may be driven by a desire to be the best, to be the top dog, to be the “alpha”.

There’s another reason, though. Some people simply have nothing better to do, so they take the path that feels either the most interesting, or the easiest. In a way, if something is easy for you, it might make it a great deal easier to master, especially if you have the right obsessive personality.

Psychologist Carol Dweck’s research on mindset provides valuable insight here. Her studies reveal that those with a “growth mindset”–who believe abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work–are more likely to achieve mastery than those with a “fixed mindset” who believe talents are innate. The growth mindset creates resilience through failure and a passion for learning rather than a hunger for approval18.

My pet theory is that you need both a combination of the right attributes (call that innate talent) and the right mindset (call that grit) to become a master.

Practical Steps Toward Mastery #

For those serious about pursuing mastery, research suggests several practical approaches:

Establish clear goals: Break down the larger ambition into specific, measurable objectives that provide clear feedback on progress.

Create accountability systems: Use coaches, mentors, or structured programs that provide external motivation and expert guidance.

Embrace discomfort: Deliberately practice at the edge of your capabilities where mistakes are common but growth is fastest.

Develop reflection habits: Regular analysis of performance identifies specific areas for improvement rather than generalized practice.

Build sustainability: Design practice routines that can be maintained consistently over years rather than intense bursts followed by burnout.

Focus on process over outcomes: Enjoying the journey itself creates intrinsic motivation that fuels long-term persistence.

Also remember to get a good night’s sleep.

For me, I have lately been fairly obsessed with practicing mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and improving my overall mental state. I want to master myself, and I want to be the best version of myself that I can be. I like to write about it along the way, and let me tell you: I have a very long way to go.

Perhaps that’s the final insight about mastery–it’s not really about reaching a destination but about embracing a particular way of being. As Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki said, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s mind there are few.” True masters never stop seeing themselves as students of their craft19.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. ↩︎

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. Scribner. ↩︎

Wolff, C. (2001). Johann Sebastian Bach: The learned musician. W. W. Norton & Company. ↩︎

Quinn, S. (1996). Marie Curie: A life. Addison-Wesley. ↩︎

Grover, T. S., & Wenk, S. (2013). Relentless: From good to great to unstoppable. Scribner. ↩︎

King, R. (2003). Michelangelo and the Pope’s ceiling. Penguin Books. ↩︎

Ibarra, H. (2004). Working identity: Unconventional strategies for reinventing your career. Harvard Business Press. ↩︎

Coyle, D. (2009). The talent code: Greatness isn’t born, it’s grown. Here’s how. Bantam Books. ↩︎

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper Collins. ↩︎

By “Copyright by Warner Bros. Inc.” - Originally published as a publicity photo (see “other versions” below)., Public Domain, link. ↩︎

LoBrutto, V. (1999). Stanley Kubrick: A biography. Da Capo Press. ↩︎

Swafford, J. (2014). Beethoven: Anguish and triumph. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ↩︎

By Napoleon Sarony - postcard (radiographics.rsna.org), Public Domain, link ↩︎

Seifer, M. J. (1998). Wizard: The life and times of Nikola Tesla. Citadel Press. ↩︎

Barlett, D., & Steele, J. B. (1979). Empire: The life, legend, and madness of Howard Hughes. W. W. Norton & Company. ↩︎

Bazzana, K. (2003). Wondrous strange: The life and art of Glenn Gould. Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. ↩︎

Suzuki, S. (2011). Zen mind, beginner’s mind. Shambhala. ↩︎