Stop Catastrophizing

Table of Contents

I was recently banned from Rover, a specialized craigslist website for finding pet sitters and dog walkers. They didn’t specify why exactly, though I know the walker claimed my dog bit her. I find this claim suspicious since my dogs have never bitten anyone before, certainly not hard enough to break skin, and her story contained several inconsistencies.

However, this post isn’t primarily about my Rover ban–as entertaining as the story might be–it’s about how my brain immediately jumps into anxiety mode and starts catastrophizing when situations like this occur.

Why the Brain Does This #

We are apes who evolved to come down from the trees and start using tools and fire, and we began cooking food and eating tubers that made our brains grow enormous relative to our bodies. But our brains are still wired to be on the lookout for danger, and when something bad happens, we go into fight or flight mode. This is a survival mechanism that has been hardwired into us for millions of years.

Evolution happens very, very slowly, but we have sprinted ahead of it with our technologies. Anxiety is–in part at least–a defense mechanism that is left over from a much more harmful and cruel reality where if you injured yourself seriously you were very likely to die, and if you were banished from your tribe you would die alone in the wilderness. So when something bad happens, our brains go into overdrive and start imagining all the worst possible outcomes. This is a survival mechanism that has helped make us the most successful (and terrible) animal on this planet, and why we have successfully eliminated some 83%1 of all the other mammals (which is not a good thing, but it speaks to a certain kind of superiority).

Our amygdala—the almond-shaped region of the brain responsible for processing fear—responds to threats about 120 milliseconds before our conscious mind even recognizes them. This lightning-fast reaction helped our ancestors survive, but in our modern world of social threats rather than physical ones, this same mechanism often misfires spectacularly.

You can actually feel catastrophizing happening in your body—your heart rate increases, your breathing becomes shallow, your muscles tense up, and you might even feel a knot in your stomach. Recognizing these physical signals is the first step to interrupting the cycle.

How to Stop It #

Stopping this is much easier said than done. There are some techniques we can use, like practicing mindfulness, or learning more about CBT, or reading the stoics. However, all these rational thinking techniques can easily be overridden by our animal instincts in times of stress.

Thus, it requires conscious effort and practice to stop the catastrophizing. In my case, I know that I don’t actually need someone to walk my dogs every day, they will be fine and they have a safe home with their needs met. But I don’t love leaving them alone for long periods, and I feel better knowing they get some time outside with fresh air and a bathroom break on days when I’m away from home for more than a few hours.

One effective technique from cognitive behavioral therapy is the “downward arrow” method. When catastrophic thoughts emerge, ask yourself: “What if this worst-case scenario actually happened? What would I do?” Following this thought process to its conclusion often reveals that even the worst outcomes would be manageable—not ideal, but not the end of the world either.

Rover is just one website, and there are not only other websites, but also other ways to find walkers (I’ve met some at dog parks before, for example, and you don’t need a website’s permission to have a conversation with someone in a public space). So really it’s just a minor annoyance, and Rover’s loss because they won’t receive any more money from me.

The Rover Story #

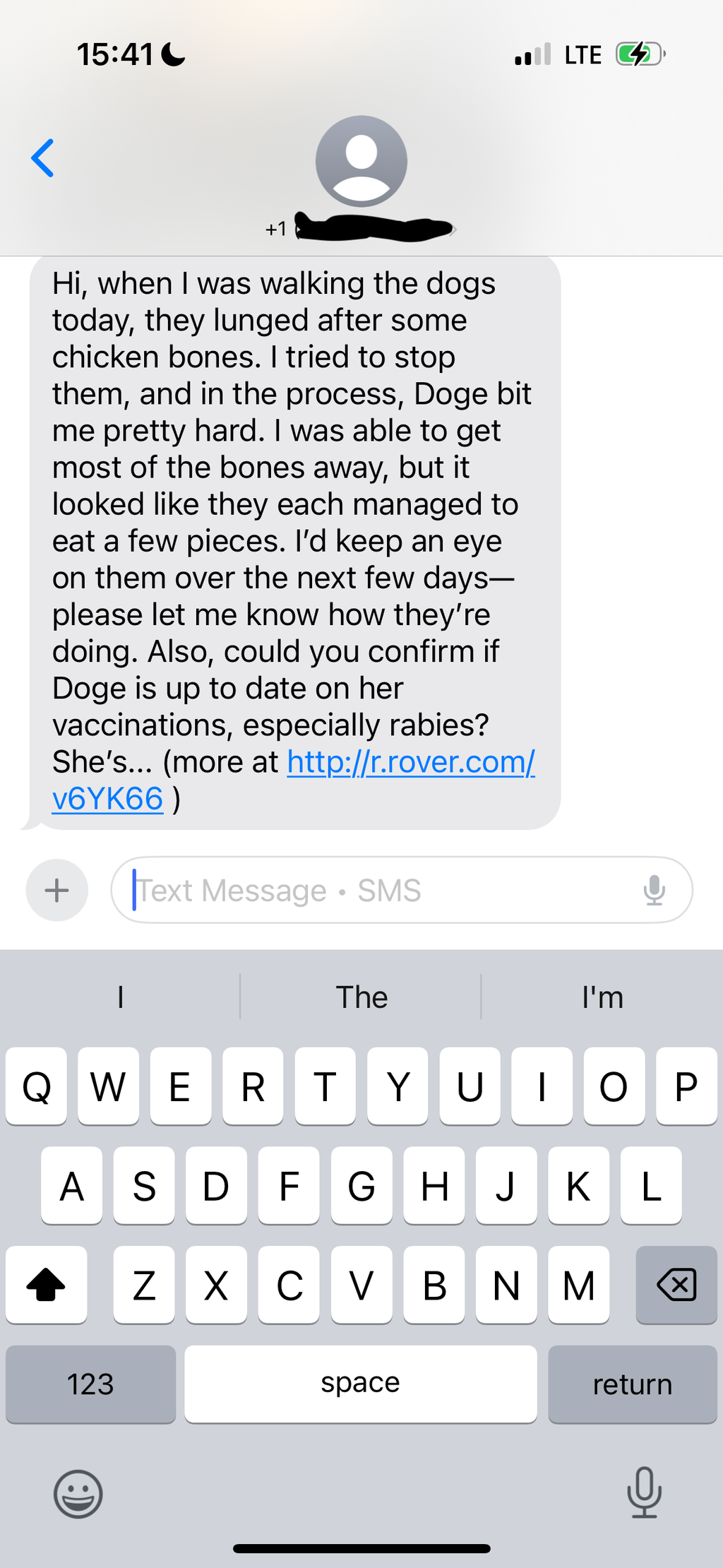

I’ll share some more details about the Rover story for those who are curious. I got the following message from the walker one day:

Hi, when I was walking the dogs today, they lunged after some chicken bones. I tried to stop them, and in the process, Doge bit me pretty hard. I was able to get most of the bones away, but it looked like they each managed to eat a few pieces. I’d keep an eye on them over the next few days— please let me know how they’re doing. Also, could you confirm if Doge is up to date on her vaccinations, especially rabies?

For those who don’t know, Doge is my dog, and Walter is my other dog. Doge is the one who allegedly bit the walker.

In response to this incident, I would say first of all that you should never stick your hands in a dog’s mouth, especially when they have food. And you should especially never do this when the dog is not yours. I don’t know exactly what she did, and if she was trying to pry the bones out of their mouths, but I can tell you that my dogs are not aggressive and they wouldn’t bite but they also wouldn’t like it if someone was trying to take food out of their mouths.

To be perfectly clear, I am going to give the walker the benefit of the doubt by taking her at her word and assume that the incident did indeed occur, and for that I apologize to her on behalf of Doge, and would caution her against ever putting her hand in a dog’s mouth again, especially when a dog finds one of those delicious chicken-bones-a-plenty on the streets of New York City. Dogs don’t have the same understanding of food safety that we do, and they will eat anything they can get their mouths on with little regard for your hand if it gets in the way.

Back to the story: I expressed my concern for her well-being, and told her that she should just let them have the bones if it happens again in the future. Then, a little while later, I get a message from the Rover “Trust and Safety” team, which contained the following:

Hi Brenden,

My name is [redacted] with Rover’s Trust & Safety team. I wanted to follow up with you in regards to Walter and Doges’s[sic] recent stay with [the walker]. As pet parents and sitters ourselves, my team completely understands how difficult these situations can be. In the instance that a pet bites someone or causes an injury, we like to gather as much information as possible to ensure we’re upholding our commitment to the safety of our community.

I’ll be working with you directly to guide you through this process. My normal time in the office is 4:00 AM - 12:30 PM (Pacific Time) Monday through Friday. In the event of an incident during a booked Rover stay, we ask all parties involved to provide us with a written statement for our records. My team understands this incident may be out of character for Doge, and the insights you share may help prevent similar incidents. Please respond directly to this email with as much information as you can provide, including (but not limited to) answers to the questions below. Your responses may be shared for the purposes of our review and to ensure the safety of our community.

- Did Walter or Doge require medical attention?

- Has your pet ever exhibited signs of aggressive behavior in the past (i.e. resource guarding, protecting, etc.)?

- If yes, did you communicate these concerns with your sitter?

- Did your sitter follow your care plan completely?

- Is there something that you, Rover, or your sitter could have done to prevent this incident or incidents like this in the future?

- What information would you like to see passed on to your sitter to provide a safer and more stress-free environment for future bookings?

- Is there anything else you’d like for us to know?

Please reply with your statement within the next 2 days. Once your response is received, please allow 48-72 hours for my team’s review and evaluation. At that time, I will reach back out to you to provide an update or request further information as needed. Please know that we do what we can to work quickly and efficiently, and your continued assistance will help us accomplish this goal.

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to let me know by responding directly to this email or giving us a call at 888-727-1140.

Sincerely,

[redacted]

Rover Support

I was a bit surprised when I got this. It’s lame that the walker decide to report me to the Rover police, but then again, people are a bit obsessed with reporting people on the Internet these days. Some have a sort of obsession with authority figures, using them as a tool for their own vengeance. They want to avoid confronting their problems head-on (guilty as charged), so they’d rather make someone else do the hard stuff rather than facing it themselves. When really, no one is coming to save you. Also, I pity the Rover employee for having to work from 4am to 12:30pm, that seems cruel and unusual.

Anyway, I responded with the following:

Dear [redacted] and the Rover Trust & Safety Team,

Thank you for reaching out regarding the incident during Walter and Doge’s recent stay with [the walker]. I appreciate the opportunity to provide more information about what happened. Please find my responses to your specific questions below:

- Did Walter or Doge require medical attention? Neither Walter nor Doge required any medical attention following the incident. Both dogs are completely fine and unharmed.

- Has your pet ever exhibited signs of aggressive behavior in the past (i.e. resource guarding, protecting, etc.)? Walter has occasionally shown mild resource guarding around his food bowl when other dogs approach during mealtime or when feeding treats. This behavior has been manageable and has never resulted in any actual biting incidents before.

- If yes, did you communicate these concerns with your sitter? Yes, I did inform [the walker] about Walter’s food guarding tendencies prior to the stay. I specifically mentioned that the dogs should be fed separately and monitored during mealtimes to avoid any potential issues.

- Did your sitter follow your care plan completely? Based on my conversation with [the walker] after the incident, it appears there was a misunderstanding regarding the care instructions. It is very common in New York City for there to be discarded food (especially chicken bones), and I don’t expect [the walker] to extract them from their mouths if they manage to get a bone (or something else). In particular, it is not a good idea for anyone to put their hands in or near the dogs’ mouths when they have food. I should have communicated this more clearly.

- Is there something that you, Rover, or your sitter could have done to prevent this incident or incidents like this in the future? In hindsight, I should have emphasized the importance of never trying to take food from them more clearly in my written instructions, perhaps highlighting it as a critical safety measure rather than just a preference. For future stays, I will provide even more detailed instructions and follow up verbally to ensure these important points are understood.

- What information would you like to see passed on to your sitter to provide a safer and more stress-free environment for future bookings? I would appreciate if sitters could be reminded to strictly follow all feeding instructions for pets, especially when multiple dogs are involved. Additionally, it would be helpful if sitters could confirm their understanding of any behavioral management strategies mentioned in the care instructions.

- Is there anything else you’d like for us to know? Despite this incident, I want to emphasize that [the walker] provided excellent care overall, and I understand that miscommunications can happen. I’ve already spoken with her about the incident, and we both have a better understanding of how to prevent similar situations in the future. I would be comfortable booking with her again with these clearer expectations in place.

Thank you for your attention to this matter. I’m committed to ensuring the safety of my pets and others in the Rover community, and I appreciate your thorough follow-up process.

Sincerely,

Brenden

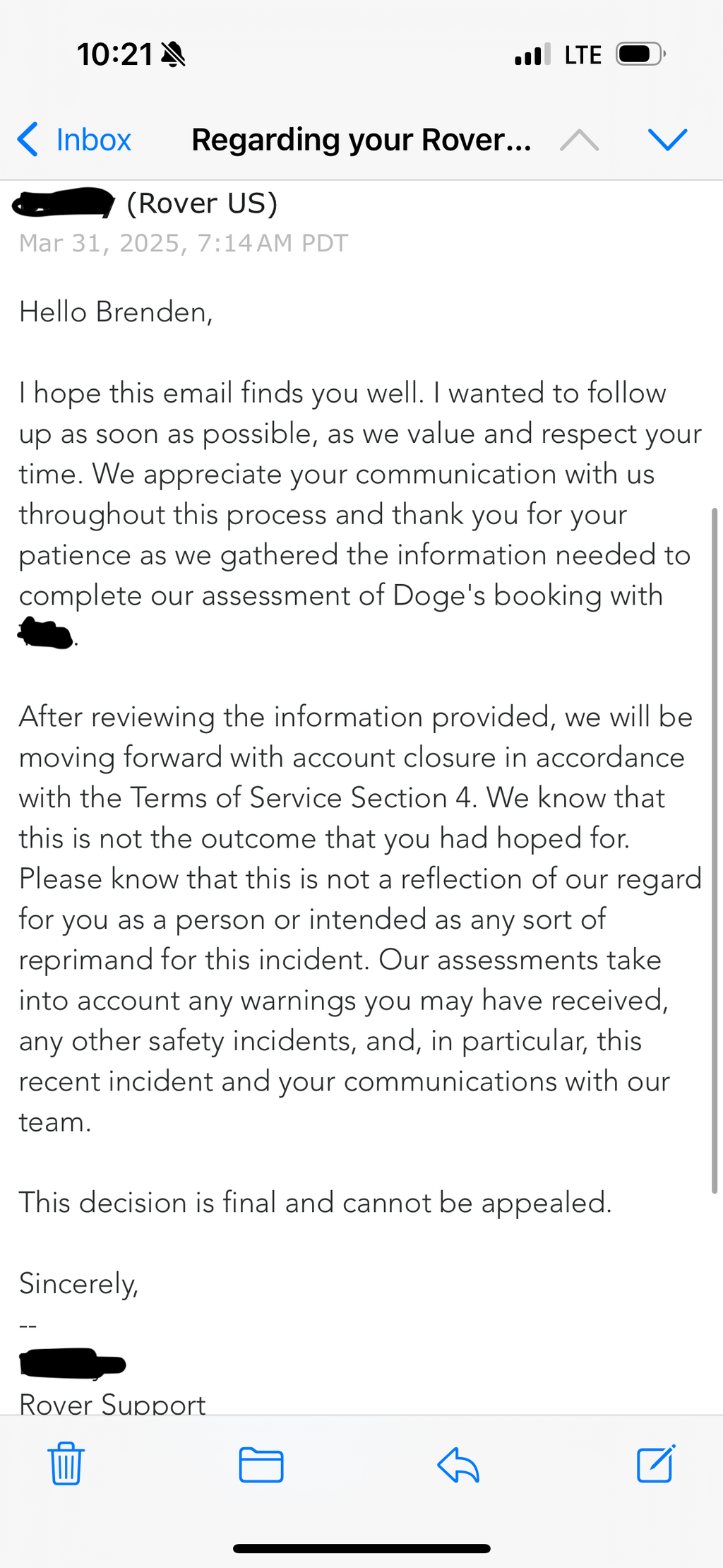

A few days later, I got a message from Rover saying that they had reviewed the incident and decided to ban me from the platform. They didn’t provide any specific reason for the ban, other than citing section 4 of their terms of service, which does not (as far as I can tell) actually apply to this situation, except perhaps as a generic blanket policy that allows them to ban anyone for any reason. The items listed in bullet points in section 4 do not apply, as far as I can tell.

The message from Rover reads as follows:

After reviewing the information provided, we will be moving forward with account closure in accordance with the Terms of Service Section 4. We know that this is not the outcome that you had hoped for. Please know that this is not a reflection of our regard for you as a person or intended as any sort of reprimand for this incident. Our assessments take into account any warnings you may have received, any other safety incidents, and, in particular, this recent incident and your communications with our team.

This decision is final and cannot be appealed.

Oh, okay then.

But Wait, There’s More #

There’s a little more to this Rover story that begins before this alleged biting incident. I had considered firing the walker for a while before this incident, but I decided to give her a second, third, fourth, fifth…and this was probably the 20th chance to redeem herself. The reason for this is:

- There were many days over the 2 months I paid for her services wherein she did not show up at all.

- On the days that she didn’t show up, she still charged me for the walking service. The Rover platform only lets the walker change the schedule, and I (as the customer) cannot change the schedule if she doesn’t show up. After Rover banned me, I did issue a chargeback by disputing the credit card charge, but that is not guaranteed to succeed should the merchant dispute my dispute.

- There were numerous days in which she did not walk both of the dogs–she only took Walter out, but I paid her to walk both Doge and Walter. I have security camera footage of her showing up, taking only Walter out for a walk, and then leaving Doge behind. Doge looked really sad on the video footage, she just sat there watching the door until they returned. The walker also sent fake photos from previous walks with Doge as proof of walking, but I could clearly see in the security footage that she didn’t walk both of them and that the photos were from a previous walk.

- She only ever walked them once around a single block, which is not in accordance with the Rover instructions. The expectation is that they would receive a 30-minute walk, but she never walked them for more than about 5-10 minutes. Better than nothing, but hardly what I was paying for.

- She (the walker) would start the walk (in the Rover app, which tracks the walk) before she even arrived at the apartment, and stop the walk after she left. I checked the timestamps on the app and the security footage, and she was starting the walk before she even arrived at my apartment.

- She claimed that Doge was trying to bite her when she tried to put her leash and collar on, but when I reviewed the security footage, I could see that the dog was just trying to get away from her, and there was certainly no evidence of biting.

- I had to take time off work to meet her and show her how to walk the dogs, which was inconvenient for me.

- She also had a habit of showing up late, which isn’t a big deal, but it was annoying.

All in all, I should have fired her in the first week when she failed to do the one simple task that she was paid to do. Instead, I gave her nearly 2 whole months to redeem herself, and she never did. I was also kind enough to not report her to the Rover police for being a shitty walker (you are welcome, but also it’s not my job to do Rover’s job).

Take a Step Back #

Back to the not-a-story part of this story.

When I received the message from Rover that I was banned, I went into a short-lived tailspin. But, on the bright side, this 2-month long thorn in my side has finally been removed. It’s annoying that I have to find a new arrangement, but my dogs will be fine. I love them deeply and I don’t like that they will be alone all day, but they are safe and happy.

What’s fascinating is that psychologists have found we’re typically much more resilient than we expect. Studies show that people consistently overestimate how bad they’ll feel after negative events and how long those bad feelings will last—a phenomenon called “impact bias.” Our psychological immune system is remarkably effective at helping us adapt to new circumstances, even unwelcome ones.

When catastrophizing, we tend to make poorer decisions because our judgment is clouded by emotional reactivity. The fight-or-flight response narrows our thinking to immediate threats, making it hard to see creative solutions or silver linings. This is why taking that step back is so crucial before making any decisions in a heightened emotional state.

Sometimes the Trash Takes Itself Out #

I think one reason I didn’t fire her sooner (which I should have) was that I didn’t want to have to confront the challenge or chore of having to find another walker, train them on my dogs, and deal with the risk of whatever BS the next person might bring into my life. It’s a “better the devil you know” kind of situation, where familiarity is sometimes easier even if the situation is not optimal.

In this case, the forces of the universe have intervened and removed this person from my life. I didn’t have to fire her, but I still need to deal with the poor service and find a suitable replacement. By delaying action on this, I only made the situation more difficult for myself, because now I have one less avenue to find a new walker. Rover’s loss.

Behavioral economists call this tendency “status quo bias”—our preference for the current state of affairs, even when change would benefit us. We tend to overvalue what we already have and fear potential losses more than we value potential gains. It’s one of the many cognitive biases that can keep us trapped in suboptimal situations.

Defeat the Lizard Brain #

We humans aren’t particularly special compared to the other animals, except that we do have this gigantic brain and we have the ability to control our body temperature through sweating (which makes humans relatively unique in the animal kingdom2).

It’s important to actually utilize this brain we have, and we need to understand how it works and why it works the way it works. My Rover ban triggered my anxiety and I started catastrophizing the situation. But I know that this is just my lizard brain trying to protect me from danger, and I need to take a step back and look at the situation rationally. In this case, I’m not in danger, it’s just a mild inconvenience. The lesson from this is that when the brain goes into panic mode, I always need to stop and think about the situation and remember that it’s probably not worth panicking over. Easier said than done, however.

One helpful visualization technique is to imagine your thoughts as clouds passing across the sky—you can observe them without becoming them. This mental distancing helps create space between you and your catastrophic thoughts, allowing your prefrontal cortex (the rational part of your brain) to regain control from the amygdala.

Practice #

Like any skill, practice makes perfect. Practicing mindfulness, self-awareness, and rational thinking is a skill like any other. Learning to recognize the negative thought patterns and how to overcome them is a core tenet of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The more you practice, the better you get at it. And the more you practice, the easier it becomes to recognize when your brain is going into panic mode and to take a step back and look at the situation rationally.

One particularly effective practice is the “3-3-3 rule” for anxiety: Name three things you can see, three things you can hear, and move three parts of your body. This simple grounding technique activates your sensory awareness and interrupts the catastrophizing cycle by bringing you back to the present moment.

I also find box breathing to be incredibly helpful. Box breathing is a simple technique where you visualize a box, and you count around the box as you breath in, hold, breath out. Inhale-2-3-4, hold-2-3-4, exhale-2-3-4, hold-2-3-4. Repeat this for a few minutes and it will help calm your mind and body. It’s also just a general good practice even when you feel great, and it can help you get into a better state of mind.

This approach works beyond dog-walking drama—I’ve used these same techniques when facing work challenges, relationship issues, and even health scares. The pattern is always the same: initial panic, conscious intervention, realistic assessment, and finally a return to emotional equilibrium. With practice, the time between panic and equilibrium gets shorter and shorter.

So stop catastrophizing, because unless bombs are actually falling on your head, it’s probably going to be all right in the end. And if it’s not all right, then it’s not the end, we are incredibly resilient, as shown by the fact that we dominate this planet (hell yeah, go humans! we have obliterated all you other mammals). Have some faith in yourself.