Nobody Wants to Hire Anymore

You’ve probably heard about the “labour shortage” everywhere. But what’s really happening in the job market? There are many theories floating around—early retirements, COVID deaths, government stimulus making people flush with cash—but the data tells a more nuanced story than these simple explanations suggest.

Let’s explore what the numbers actually show about the current state of the labour market.

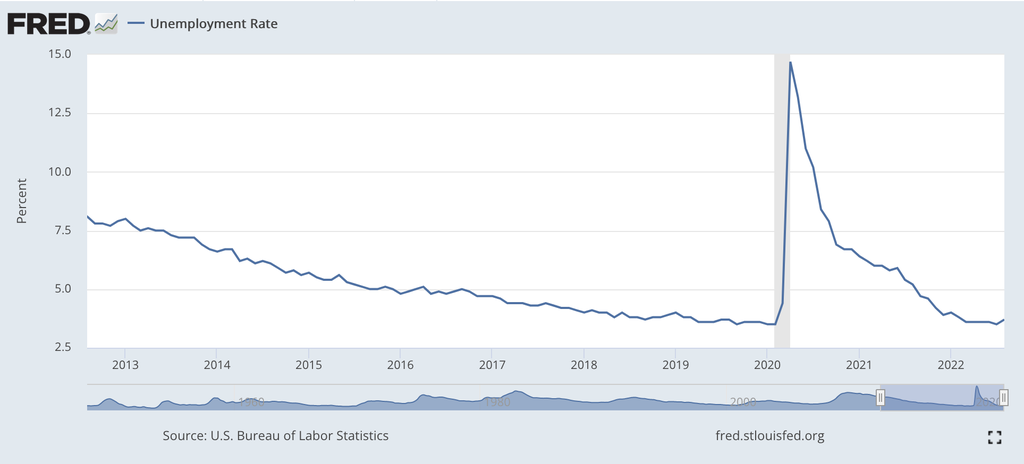

First, let’s look at the unemployment rate:

Interestingly, unemployment is still slightly above pre-COVID levels (3.7% vs 3.5%). The difference is small but notable. Now, what about the labour participation rate?

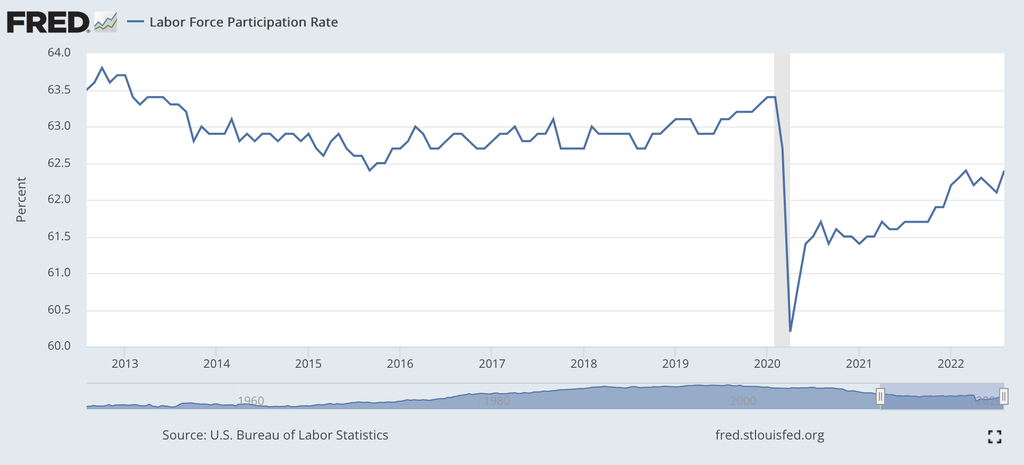

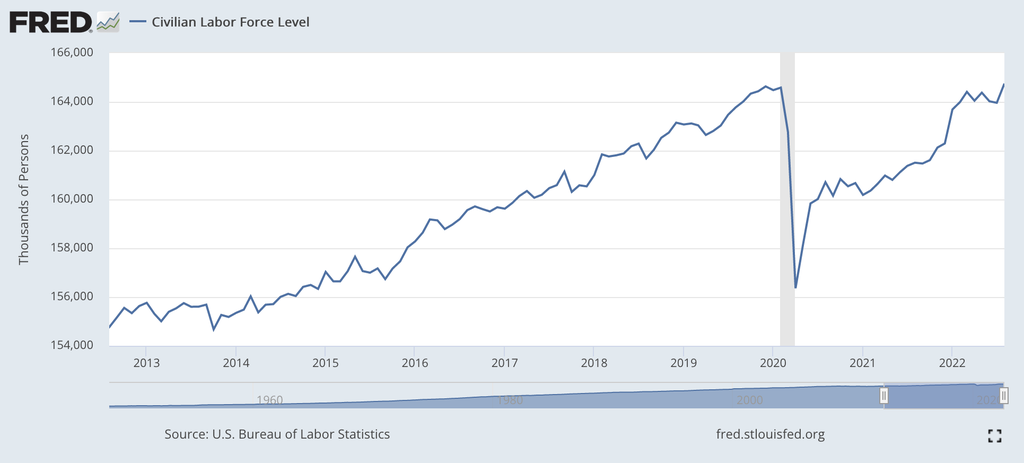

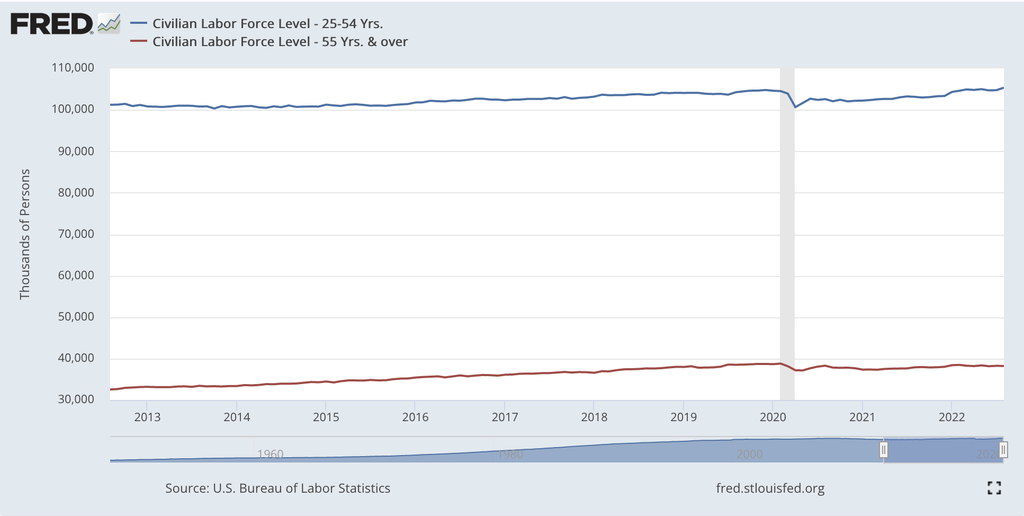

Here we see the pre-COVID participation rate was 63.4% versus 62.4% today—a 1% difference that represents about 3.3 million people out of the workforce, assuming a population of 330 million. But does this mean fewer people are working? Let’s check the labour force level (the number of people in thousands in the labour force):

Surprisingly, the pre-COVID peak was 164.6 million, and currently it’s 164.7 million. There are actually about 113,000 more people in the labour market now than before the pandemic.

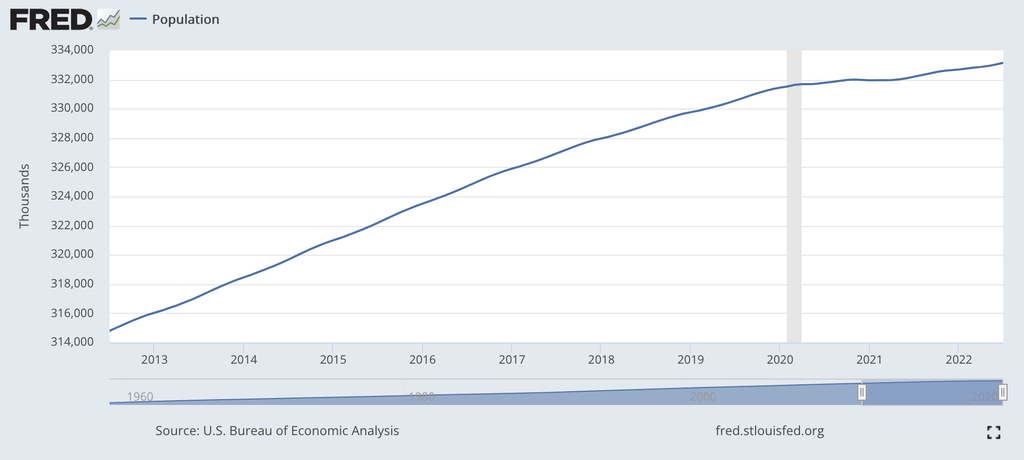

So why is the participation rate lower if more people are working? Part of the answer lies in population growth. The US population has increased:

Pre-COVID population was about 331.5 million, versus 333.1 million today—an increase of about 1.612 million people.

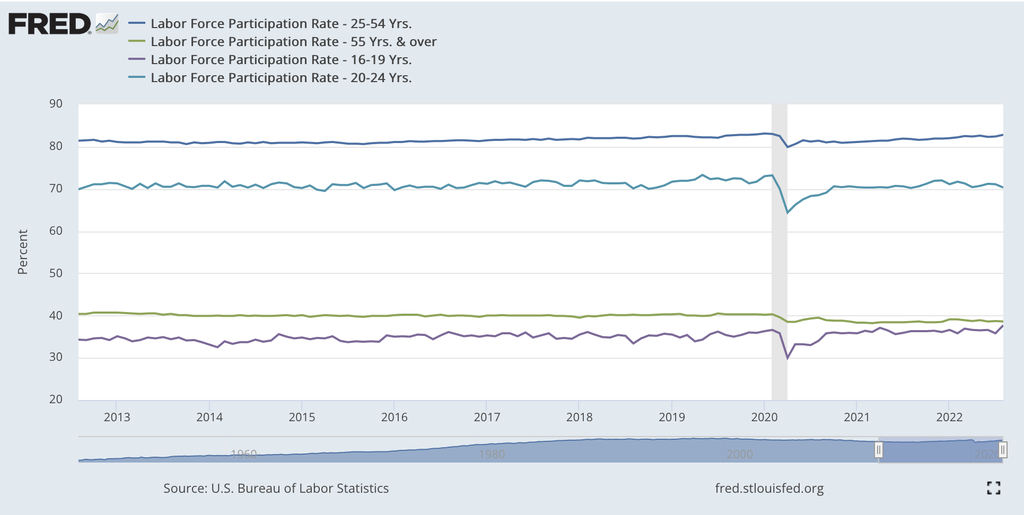

Breaking down participation by age reveals more insights:

For the over-55 cohort, there’s a modest drop in participation (from 40.3% to 38.6%), which partially supports the “retirement” narrative. Looking at absolute numbers:

There are 38.2 million people over 55 in the labour force now versus 38.7 million pre-COVID—a difference of about 560,000 fewer older workers. However, younger cohorts have more than made up for this decline.

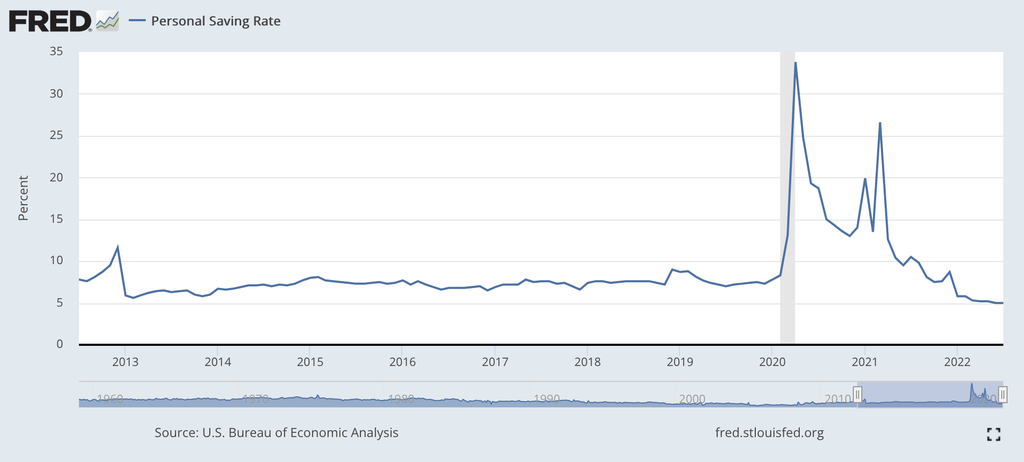

Are people staying out of work because they have too much money saved? The personal savings rate suggests otherwise:

Savings are actually down significantly from pre-COVID levels. The pre-COVID rate was 8.3%, and today we’re at 5%—a 40% decrease!

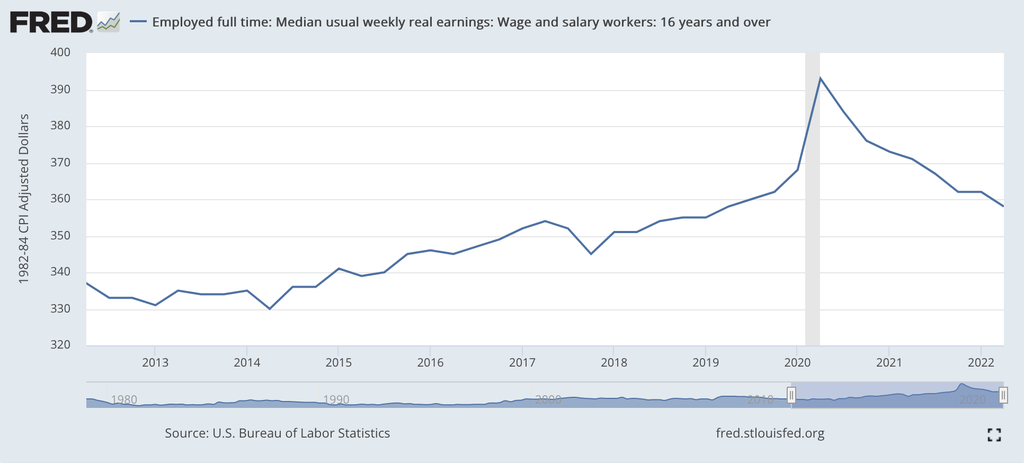

What about wages? Let’s examine real wages:

Contrary to popular narratives, real wages (adjusted for inflation) have declined from their pandemic peak and are now below pre-COVID levels. The temporary spike during COVID likely reflects the disproportionate job losses among lower-wage workers, which mathematically increased the average.

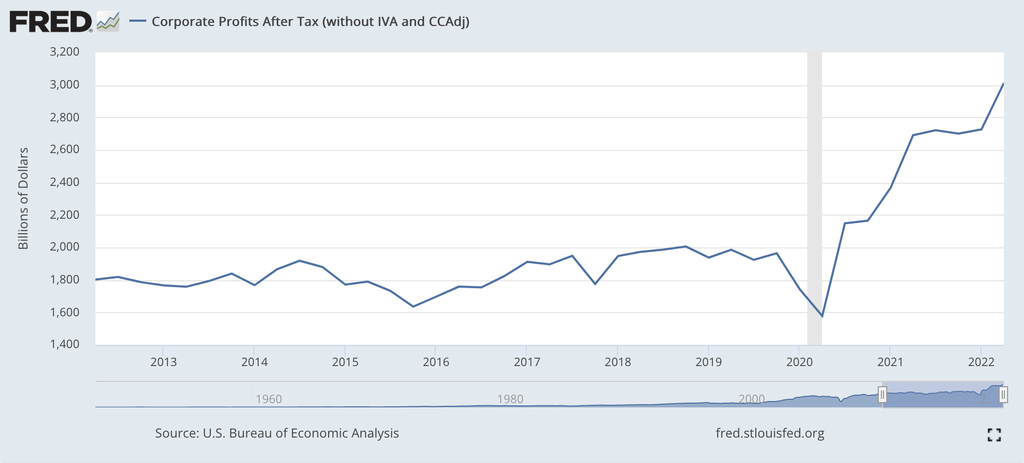

Finally, let’s look at corporate profits:

Corporate profits have increased approximately 50% over pre-COVID levels, raising interesting questions about resource allocation in the economy.

Here’s what we can deduce from this data:

- Corporate profits are up about 50% compared to pre-COVID levels

- Personal savings are approximately 40% lower than pre-COVID

- The total number of people in the labour market has increased slightly

- Real wages have declined since their pandemic peak

- Unemployment remains low, though not quite as low as before COVID

- Overall labour participation rate has decreased, despite more total workers

- The population has grown by over 1.6 million people

This data suggests that rather than a simple “labour shortage,” we’re experiencing a market adjustment where wages haven’t kept pace with changing worker expectations and living costs. Many businesses appear reluctant to increase compensation to the levels that would bring sidelined workers back into the labor force.

What might this mean for the economy going forward? As interest rates rise, we may see pressure on overleveraged businesses and individuals, potentially affecting both hiring and wages. Inflation concerns will likely continue as companies adjust pricing strategies.

The economic outlook contains both challenges and opportunities. Businesses that adapt to the new realities of the labour market—offering competitive compensation, flexibility, and growth—will find themselves better positioned to attract talent and thrive in this evolving environment. Meanwhile, workforce development programs and policy changes may help address the structural mismatches in the labour market.

For individual workers, developing in-demand skills and being strategic about job choices becomes increasingly important in navigating this complex landscape.