More Is Worse

Table of Contents

You’ve heard the phrase “less is more,” but have you ever considered its mischievous cousin: “more is worse”? It’s the same idea, just with a sharper edge. My favourite example? Restaurant menus. The worst restaurants always seem to have the most options. When I go out to eat, I want the chef to present their best dish—no decisions, no stress. The chef already knows what’s good. Just put it in front of me (ideally, a steak). The ultimate luxury is when someone knows exactly what you want and simply delivers it.

Yet, we spend our lives being sold the opposite: that more is always better. Capitalism whispers that happiness is just one more purchase away. But once your brain matures a bit, you realize the truth: more is often just… worse.

Whether it’s money1, stuff, food, or friends, I’d rather have a small collection of high-quality things than a mountain of mediocrity. A few good friends beat a crowd of acquaintances. One perfect croissant is better than a dozen stale bagels.

The Paradox of Choice #

Psychologist Barry Schwartz coined the term “paradox of choice” to describe how having more options can actually make us less happy. His research found that while we think more choices will make us happier, they actually lead to anxiety, indecision, and regret. We’re haunted by the thought that maybe, just maybe, we picked the wrong thing.23

This is why the 24-page diner menu—pancakes, pasta, prime rib, sushi, and maybe a taco—almost always signals mediocrity. No kitchen can master hundreds of dishes. But a restaurant with five carefully crafted options? That’s a place that’s honed its craft. Constraint becomes a superpower.

The best meals I’ve had were at places with limited menus—often prix fixe, sometimes omakase—where you make zero choices (my favourite), or maybe pick between two options in a many-coursed meal (think The French Laundry). In New York City, omakase is currently quite trendy, and while some folks are in it for the Instagram, the chefs running these places truly “get it.” Omakase literally means “I leave it up to you”—and the “you” is the chef.

As psychologist Barry Schwartz puts it in his book on the subject, the downside of too much choice can be profound:

As the number of choices grows further, the negatives escalate until, ultimately, choice no longer liberates, but debilitates.

Deep.

The Digital Overwhelm #

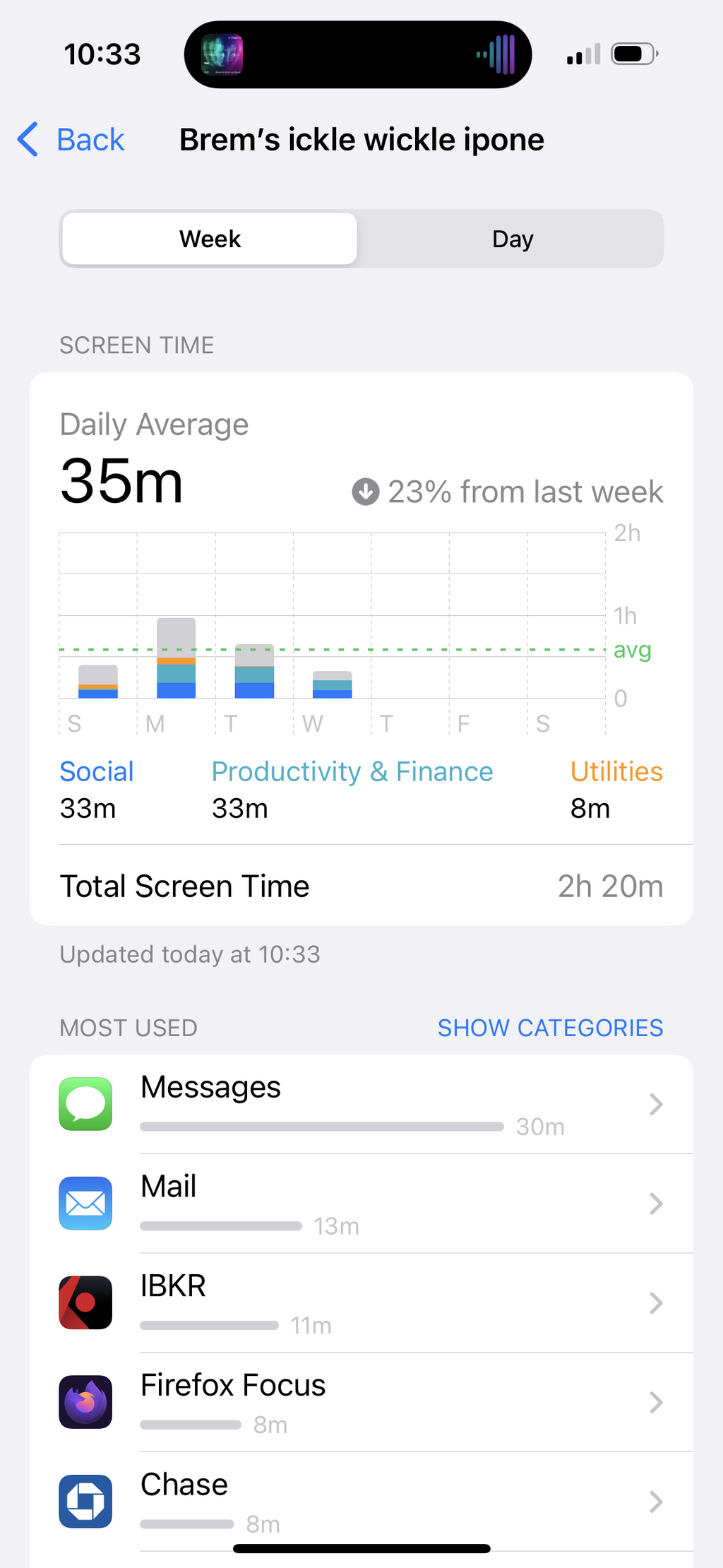

The average smartphone user has about 80 apps installed but regularly uses only 9 or 10.4 Streaming services offer thousands of shows, yet we often spend a frustrating amount of time scrolling just trying to decide what to watch.5 Social media feeds are infinite, but leave us feeling empty, not enriched.

Still too much screen time.

I not-so-recently deleted most of my social media accounts and kicked my news addiction. Honestly, it wasn’t hard—most mainstream media is garbage. Now, I check in occasionally, but only from a desktop browser with aggressive ad blocking. The effect was immediate: a mental clarity I hadn’t felt in years. The constant, low-grade anxiety of “missing something important” vanished when I realized most of what I was consuming wasn’t important at all.

The relief is profound. Get addicted to something good instead—yoga, volunteering, contributing to open source software, whatever. Focus on one thing and do it well. It’s rewarding–and who knows, maybe you’ll one day master that thing?

It’s not just me: research shows that excessive digital technology use is linked with higher stress, reduced attention span, poorer sleep, and less time spent in-person, which diminishes mood and well-being. High levels of online multitasking and information overload are correlated with increased anxiety and chronic stress. Both very high and very low levels of digital engagement are associated with decreased well-being; moderate, intentional use fares best. In-person interactions, which are key to well-being, are often crowded out by digital distraction, with studies linking screen time to diminished social skills and empathy.46

Kick your virtual reality habit by deleting those apps, and try reality reality.

Quality Over Quantity in Relationships #

Nowhere is “more is worse” more obvious than in our social lives. Research shows it’s the quality, not quantity, of relationships that matters. A 2010 Harvard study found that a few deep, meaningful friendships predict happiness and life satisfaction far better than a crowd of acquaintances.7 More recent research confirms that deeper, meaningful relationships yield greater satisfaction and emotional health than numerous superficial contacts. Excessive social or dating app options can actually amplify choice paralysis and reduce relational satisfaction, as users fear missing out on “better” options. In digital environments, prioritizing genuine connection over volume of interaction aligns with greater happiness and lower rates of loneliness.89

I can personally vouch for what the research says. After stepping away from dating apps, I can’t claim to be any more successful at meeting people offline—but I am undeniably happier. The constant cycle of swiping, rejection, ghosting, and feeling like you’re never quite enough (because there’s always the illusion of someone better out there) is exhausting. Letting go of all that pressure has been a relief. And honestly, being single has its perks—like total freedom, and, well, the internet is always there if you need a little company.

Doge, the realest of friends.

Dreadful dating app experiences aside, I’d much rather spend an evening in deep conversation with a close friend than make small talk at a crowded party. Real connection just isn’t possible when your attention is scattered. Honestly, I’m just as content hanging out with my dogs, who I share a deeper bond with than most people I know. My favourite thing about weekends is that I get to spend uninterrupted quality time with them, with not a care in the world other than making sure everyone gets enough pets.

Mindful Consumption #

Minimalism keeps resonating because it’s an antidote to the exhaustion of too much choice and stuff. When we have fewer possessions, each one is something we genuinely value. When we consume less media, we engage more deeply with what we do consume.

Walter, destroyer of furniture and anything else he can get his jaws on.

Take a cue from my dogs: learn to enjoy less. Walter is thrilled chewing on a piece of furniture, and that doesn’t cost extra. I’ve started applying a simple filter to most decisions: will having more of this genuinely improve my life, or just add complexity and maintenance? More often than not, restraint wins.

This isn’t about living an austere life—quite the opposite. It’s about making space for abundance in what truly matters by cutting back on what doesn’t. The fewer distractions we have, the more we can appreciate what remains.

There’s a richness to simplicity that no amount of money can buy. Research shows that decluttering and reducing possessions measurably improves mental clarity, focus, and reduces stress. Minimalist environments are associated with better air quality, fewer allergens, and improved physical health. A minimalist lifestyle supports mindful consumption: individuals tend to buy higher-quality, longer-lasting items and experience more satisfaction and less decision fatigue. Simpler physical and digital environments facilitate better sleep, healthier diets, and greater productivity by removing distractions. Marie Kondo was onto something when she said that the key to tidiness (and happiness) is to keep only the things that spark joy.1011

While I wish I could afford an apartment bigger than 450sqft, it has the nice quality of forcing me to live with less. So in a way, I’m probably happier than I would be in a bigger place.

So next time you’re faced with an endless menu of options—literal or metaphorical—consider that the best choice might be the place with fewer, better options. Or just ask the chef what they do best, and trust their expertise over the tyranny of unlimited choice.

More isn’t better. More is worse. And realizing that might be one of the most liberating truths you ever discover.

I’m not saying money is bad, but it’s a good example of something that people are taught to believe more is better. Beyond a certain point, money doesn’t make you happier once you’ve met your basic needs. ↩︎

Schwartz, B. (2004). The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. ↩︎

Chernev, A., Böckenholt, U., & Goodman, J. (2015). Choice overload: A conceptual review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 333-358. ↩︎

App Annie. (2017). “The average person has 80 apps on their phone, but only uses 9 per day.” TechCrunch. ↩︎ ↩︎

Variety. (2022). “Americans Spend 10 Minutes Deciding What to Watch.” Variety. ↩︎

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271-283. ↩︎

Waldinger, R. J., & Schulz, M. S. (2023). The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. ↩︎

Sandstrom, G. M., & Dunn, E. W. (2014). Social interactions and well-being: The surprising power of weak ties. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(7), 910-922. ↩︎

Iyengar, S. S., & Fisman, R. (2005). Gender differences in mate selection: Evidence from a speed dating experiment. Psychological Science, 16(3), 267-273. ↩︎

Kondo, M. (2014). The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. ↩︎

Saxbe, D. E., & Repetti, R. L. (2010). No place like home: Home tours correlate with daily patterns of mood and cortisol. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(1), 71-81. ↩︎