Do a Bad Job

Table of Contents

As a recovering perfectionist, I’ve been learning to embrace a radical idea: it’s better to do a bad job of something than to do nothing at all. The wisdom is everywhere—you miss every shot you don’t take, perfect is the enemy of good, done is better than perfect—but living it is another matter entirely.

For me, the desire to do everything perfectly stems from a toxic belief: if I can’t do something well, it’s not worth doing at all. But I’m unlearning this lie. Yes, some people have natural talents, but even they need to practice to master anything. The rest of us? We need practice even more—and that means being willing to be bad at things first.

Besides, setting a goal to be good or great at something isn’t even the point. While it’s fine to have these goals, you can also embrace doing a thing simply because you enjoy it.

There’s an entire movement celebrating mediocrity. Sweden has a Museum of Failure showcasing corporate disasters like Google Glass and Colgate Lasagna (yes, that was real). Writers gather for “Bad Poetry Nights” to compose deliberately terrible verse. Artists meet for “Crap Art Club” where the goal is to make something awful. It’s brilliant—by removing the pressure to be good, they free themselves to actually create.

Perfectionism #

Perfectionism is rooted in our desperate need to impress others. We’re tribal creatures, hardwired to fit in. The lone wolf, the black sheep—these aren’t just metaphors but evolutionary warnings. To be rejected by the tribe once meant death. So we contort ourselves into whatever shape we think will earn acceptance, even if it means never trying anything we might fail at.

Here’s the cruel irony: perfectionism doesn’t make us better—it paralyzes us. A recent meta-analysis of 416 studies found that perfectionism is significantly linked to anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. I’ve spent countless hours planning the “perfect” approach to projects that never saw daylight. It’s a special kind of self-sabotage where the fear of doing something wrong ensures you never do anything at all.

Quality exists on a spectrum—perfect, good, mediocre, bad, terrible, abysmal. But these judgments are wildly subjective. What matters isn’t where you land on the spectrum but that you’re on it at all.

Bad Art #

Creating art provides the perfect lesson here. Everyone should make art, but many are discouraged because they don’t see themselves as artists, or they don’t think their art is any good. To be fair, many people produce terrible art, but in a sense those people are succeeding because at least they tried. They’ll probably learn from their mistakes and improve. Those who never attempt will never know whether they could have been good—or wonderfully, gloriously bad—at it.

But also, making art shouldn’t be about making good art. It should be about the process, the expression, the sheer fun of it. The end goal shouldn’t be to have your work displayed in a museum (though hats off if you manage that).

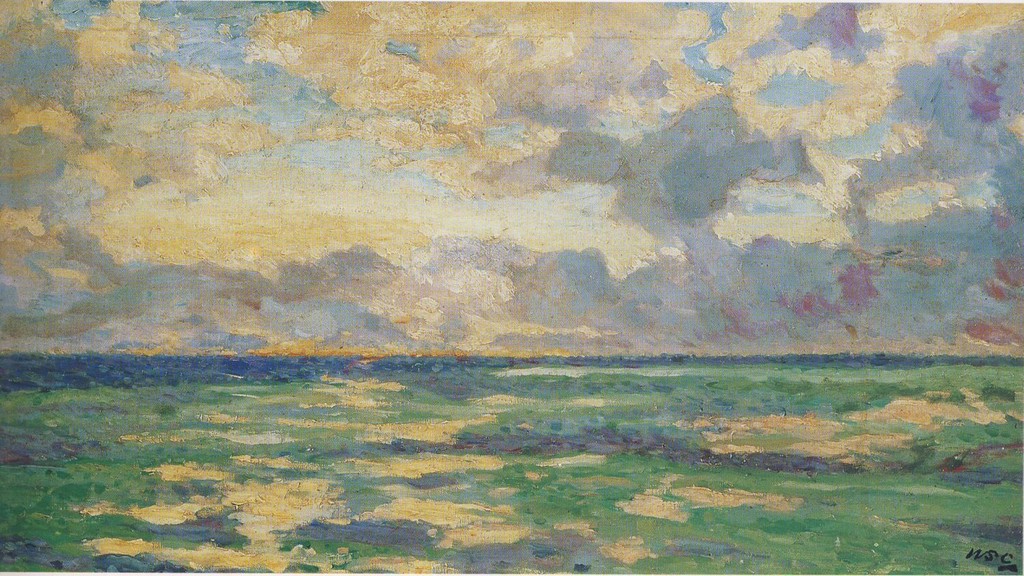

Daybreak at Cassis, 1920. Winston Churchill.

I love that Winston Churchill took up painting after getting fired from his government job following the disastrous Gallipoli campaign. He was terrible at it by most accounts, but he didn’t care. He just liked squeezing out the colors and making a mess. He created over 500 paintings, and from what I’ve seen, they’re…not great. But he kept doing it because it brought him joy during some of his darkest hours.

Other world leaders found similar solace in bad art. George W. Bush’s portraits are earnest but amateur. Jimmy Carter’s paintings have fetched hundreds of thousands at auction, though they’re far from remarkable. Dwight Eisenhower painted to relax between running a war and running a country.

Bob Ross embodied this philosophy perfectly: make happy little accidents. He rarely sold his paintings, preferring to give them away to PBS stations, students, and charities. As Bob Ross Inc. later explained, selling paintings “wasn’t really Bob’s thing”—he understood that the value wasn’t in the finished product but in the joy of creation itself. A man who understood, perhaps better than anyone, the profound value of doing things badly.

Embrace Imperfection #

My art isn’t special. It’s not Instagram-worthy or gallery-ready. But I make it anyway. I experiment, fail, try again. I embrace the imperfection because the alternative—giving up on creating altogether—feels like a kind of death.

There’s a Japanese concept called heta-uma, which translates to “bad but good.” It describes art that looks terrible on purpose but somehow becomes more interesting than technically perfect work. Sometimes the wonky, imperfect stuff has more soul than the polished pieces.

Think about it: absolute perfection doesn’t even exist. Everything has flaws—every person, every object, every story. The only perfect things exist in our imaginations, not in the material world.

I give my mediocre art prints to friends. They appreciate them—not because they’re good, but because they’re handmade, because someone cared enough to create something just for them. Maybe they don’t all hang on walls, but no one has ever told me they hate them. (Or maybe they’re just kinder to me than I am to myself.)

Feel Good #

But here’s the real reason to do things badly: it feels good. In a world that often leaves us depleted, creating something—anything—is an act of defiance. The act of creation is as fundamental to being human as eating or sleeping. It brings meaning to our lives, requires no one’s permission, and stands apart from the endless cycle of consumption and productivity. We’re told we should spend money, consume content, buy products, order delivery. We’re not encouraged to make anything (unless it’s content for a website that needs your content to sell ads alongside).

Einstein played violin terribly—when he tried to play with pianist Artur Schnabel, Schnabel reportedly exclaimed, “For pity’s sake, Albert, can’t you count?” But he kept playing because it helped him think through physics problems. The quality of his music didn’t matter; what mattered was how it served him. Sometimes being bad at something is exactly what we need.

Life offers few certainties beyond its eventual end. If something brings you joy or meaning—even if you’re terrible at it—that’s reason enough to do it. Stop optimizing for other people’s approval. Start optimizing for your own happiness.

In a world where every hobby must become a side hustle, where we’re all performing our lives for Instagram likes, doing something badly—just for the hell of it—becomes revolutionary. It’s a middle finger to the optimization industrial complex. It’s choosing joy over metrics, process over product, being over performing.

So go ahead. Write that terrible poem. Paint that ugly picture. Play that instrument badly. Do it with gusto, with pride, with the knowledge that in a world obsessed with excellence, your willingness to be mediocre is its own kind of perfection.