Bad Incentives, Bad Outcomes

Table of Contents

When examining human behavior, you can usually answer the “why?” behind most phenomena by analyzing incentives. This principle applies universally—from economics to politics, where elected officials often prioritize certain interests over broader constituent needs. There’s a reason the phrase “follow the money” has become ubiquitous.

Many people skip the step of examining incentive structures, then express confusion when others act in ways that seem counterintuitive. Yet once you look at the underlying incentives, motivations typically become clear. Most of the dysfunction we see in modern capitalism can be traced to poorly designed incentive systems.

Capitalism isn’t a force of nature—it’s a human-created system. For it to function effectively without undermining itself or society, we need thoughtfully designed incentives that align private interests with public good.

The Housing Affordability Challenge #

Housing affordability has become a pressing issue across Western nations. When examined through an incentive lens, the situation becomes clearer. Housing has become increasingly unaffordable largely because key incentives are misaligned.

Browse forums like r/REBubble or read comments on tech sites discussing housing prices, and you’ll repeatedly encounter familiar explanations:

- Restrictive zoning laws

- Short-term rentals (Airbnb)

- NIMBY opposition to development

- Excessive regulation

- Insufficient housing construction

While these factors contribute to the problem in varying degrees, they don’t represent the root cause. Even combined, they explain only part of our housing affordability challenge. If we somehow resolved all these issues tomorrow, housing would likely remain out of reach for many people.

Examining the Housing Shortage Narrative #

Let’s look at whether a genuine housing shortage exists. Using US data as an example (though similar patterns appear across developed economies):

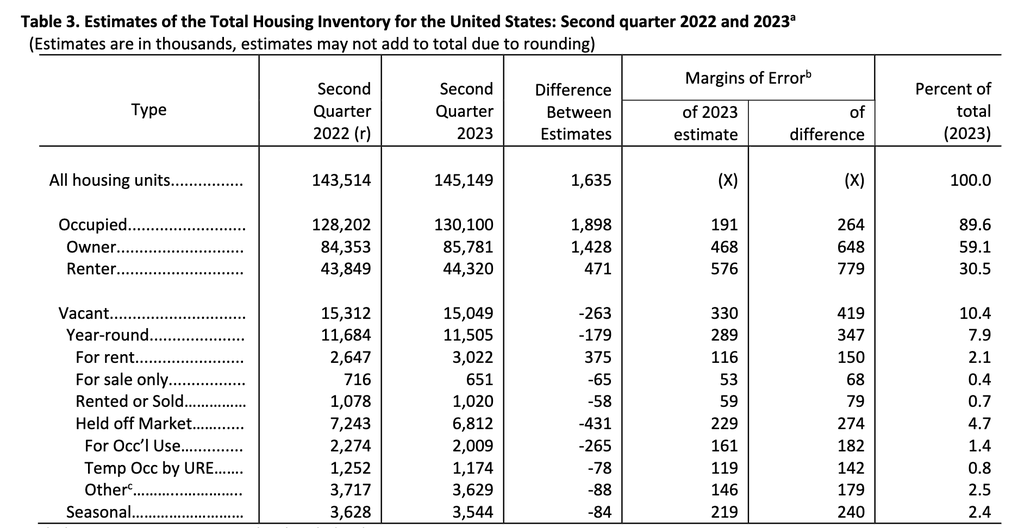

According to recent vacancy data from the US census, approximately 15 million homes currently sit vacant in America:

While definitions of “vacancy” can vary, 15 million is substantial enough to challenge the simple “not enough homes” narrative. Rather than an absolute shortage, we seem to have a distribution problem—plenty of housing exists, but not necessarily available to those who need it most.

I observe this phenomenon in New York City, where many luxury condominiums in affluent areas show few lights at night, suggesting lower occupancy rates. Meanwhile, the city also faces issues with rent-stabilized vacant units, where some landlords deliberately keep apartments off the market.

Such practices could potentially be addressed through targeted vacancy taxes and non-primary residence fees. With the right policy adjustments, much of this inventory could potentially return to the market at more competitive rates.

Certainly, some portion of these 15 million vacant homes have legitimate reasons for emptiness—renovation, transition between owners, seasonal use, etc. But at roughly 10% of the total housing stock, this vacancy rate seems surprisingly high during what’s frequently described as a housing crisis.

The Investment Vehicle Phenomenon #

If we look beyond the shortage narrative, what explains today’s high housing costs? A significant factor appears to be our system’s treatment of housing not primarily as shelter but as a subsidized, leveraged investment asset. Many property owners hold real estate assets specifically anticipating future appreciation.

Financial leverage drives housing costs upward, especially when interest rates remain historically low (even today’s Federal Reserve rate of 5.25-5.5% remains below long-term historical averages). In the American context, 30-year fixed-rate mortgages with government guarantees create a scenario where lending institutions face minimal consequences for poor risk assessment—a classic “moral hazard” situation.

Potential Housing Market Improvements #

Creating a healthier housing market would require realigning incentives. Potential approaches might include:

- Reconsidering preferential tax treatment for investment properties

- Evaluating government subsidies in the housing finance system

- Implementing meaningful vacancy taxes to discourage property underutilization

- Recognizing housing’s dual nature as both essential infrastructure and financial asset

The current market dynamics often favor those who already own property while creating barriers for newcomers. This contributes to wealth inequality as housing costs consume an ever-larger portion of income for non-owners.

The system increasingly rewards asset ownership over productivity, innovation, or other forms of social contribution. Success often correlates with market entry timing rather than merit or effort.

In essence: we should consider whether housing policies should prioritize shelter as a fundamental need or investment returns as the primary goal.

Realistically, though, significant change faces substantial obstacles. Powerful interests benefit from current arrangements, making transformative reform politically challenging.

The fundamental question remains: do we want a society where housing serves people, or one where people serve the housing market?